In case you missed it, here’s Part 1, which describes why I became a teacher and the early years of my career. Let’s continue the story…

If I were to think of my teaching career as a love story of sorts, then there are bound to be ups and downs in the relationship:

BUMPS IN THE ROAD

In education, there is always something new happening. The higher ups are seemingly ALWAYS looking for the next new thing, strategy, idea, or way of doing something. It can be overwhelming for those at the low rungs of the ladder – i.e., the teachers who are actually supposed to be doing the new things.

I started teaching high school English in 1998, and as I mentioned before, there were no academic standards in place just yet. There were “standards” set by teachers, to be sure, but they weren’t yet set in stone by the Overlords of the State. Well… actually there were standards, factually speaking (see below), but they hadn’t yet gotten to the place where they were deeply ingrained into what teachers were doing in the classroom. These things take time, which is something that education reformers and lawmakers don’t always seem to understand.

What was definitely missing, however, is that there wasn’t really a discussion – among the teachers I worked with, anyway – of what we were collectively doing in our classrooms. But there was a very high level of trust given to us teachers to be doing things that were meaningful and rigorous (God, how I hate that word now!).

In other words, just because there weren’t official standards in place yet, teachers were still expected to be designing high-quality, engaging curriculum and employing various instructional strategies that met a diverse group of students’ academic needs. It just wasn’t coming from the top; instead, it came from us, the teachers. We had true academic freedom.

The state of California first introduced English-Language Arts Content Standards in December of 1997. That’s when they were approved, anyway. It took a couple of years for the word to trickle down the ladder to us teachers, and then a couple more years for students to actually be assessed according to their knowledge of the standards – this was the start of the accountability movement in education that is still with us today.

It was 2003, to be exact, when student performance was first assessed using the California Standards Tests (CSTs). We had standardized tests before that, but they weren’t tied directly to a common set of standards. And other than giving us a snapshot of how our students were doing at a given time (usually April), these standardized tests didn’t have any consequences for schools (there were no high stakes at this time). Students received their scores via mail at the end of the summer, and schools received their scores at the same time. We looked at them, maybe analyzed them for a minute – or an hour – at a pre-school inservice day, and then moved on. Nothing important to see here, folks! All this was fine with me. I, too, had taken standardized tests once a year in school. I liked getting my score report in the mail to see if I had done better than the year before. But I never put much meaning in them because they didn’t really count for anything. They weren’t high stakes.

Anyway, back to the standards. I liked that the standards provided some focus. I liked that we still had that academic freedom I mentioned. I also liked that we were starting to talk to each other more about what we were doing in our classrooms – we were even starting to plan together. I was involved in some pretty cool professional development around the time we were starting to work with the standards. From 2001 to 2003, I, along with a team of teachers from my school (Mar Vista High), took part in a program with the California Academic Partnership Program (CAPP) and the Western Assessment Collective (WAC) where teams of teachers worked to develop standards-based instructional units. This site describes the program I was a part of, but sadly, the links to the units we designed aren’t working anymore.

What I took away from this process was: 1) real teachers (not faceless corporations) were the creators of these curriculum units, 2) we kept them student-centered and realistic, 3) we had in-depth discussions of what the standards meant (called “unpacking” the standards), how they could best be assessed (and guess what? the answer was almost always NOT by multiple-choice tests! Shocker!), and how they could be taught to a diverse group of students at different levels. We were covering all the important topics – teacher creation of high-quality lessons and assessments, differentiation, standards, planning lessons together (which would later officially be called a professional learning community) – we were far ahead of the game! And it was a fun process as well. We met for several days in the summer and then during the school year for three years doing this work with CAPP/WAC. Part of what made it meaningful was that it did take so long, because again, real change takes time to take hold. We became better teachers as a result of this process, and those skills stayed with us for our careers.

I want to clarify something about these new standards – this will be important later in my discussion, and maybe more so in PART 3 — Before they came along, and I’ll just speak for myself here, I was already doing good things in the classroom. And I was reflecting regularly on my teaching, looking at how I could improve it the next time. So when the standards arrived and I was told to start implementing them, I simply looked at what I was already doing and then matched up different standards to existing lessons, activities, and assessments. After I went through the PD I described above, I gained more focus on what I was doing and used the standards to refine my teaching. An example: pre-standards, I would “teach Romeo and Juliet” to my 9th graders. Post-standards, I would “teach characterization using Romeo and Juliet.”

So the way the standards helped me most was to give me and my colleagues more focus and refinement in our teaching. And I did actually like that, since I’m a rather orderly kind of person (and that may be a bit of an understatement). After this experience, my colleagues and I were doing a lot more planning together and trying to make our students’ experiences a bit more uniform with each other. For example, we agreed upon a list of novels that we would definitely teach at each grade level. And we designed common essay prompts. In fact, we designed common diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments and began looking at student work together, which was very beneficial for us as professional educators. I also liked that we still had plenty of academic freedom to teach how and, for the most part, what we wanted. We were just ensuring more equity in the academic experience each of our students had at each grade level.

From this point of view, the California ELA standards weren’t terrible, especially since I felt I had a good amount of time to adjust to them. (And compared to what came later with Common Core – they weren’t bad at all!)

But in 2001, California adopted AB 466, which established the Mathematics and Reading Professional Development Program. How this affected me and my fellow English teachers is that we were required to be trained in the new statewide ELA textbook adoption that occurred in 2005. This was new for English teachers in several ways – 1) statewide, districts had to choose the ELA textbooks from a state-approved list (a rather small list to begin with), 2) it is my understanding most districts chose the Holt textbooks, meaning that statewide most English teachers would be using the same materials, and 3) teachers were required to attend the training (we even got paid to attend the 5-day summer training) AND actually use the new textbook materials. We had to attend 40 hours of this training, and then told we must use these materials “with fidelity.” This was seen by the teachers I worked with as very harsh. We could no longer use supplemental materials we already had; no, we HAD to use the new textbooks. This was a huge change from my first year teaching when I was given a textbook and told to use it if you want. We lost a lot of autonomy with this bill, though I am not totally certain that was the intent. Or was it?

One big part of the problem was that we were supposed to stop teaching novels. Yep. Full stop. They didn’t fit into the “red line” of what we were supposed to be doing. The “red line,” as we called it, was from the Holt pacing guide. See, the publishers stuffed a whole lot of material into a school year that realistically could NEVER be covered, and then they selected the most important texts that must be taught and put them in RED – hence the name the “red line.” Now, there weren’t necessarily any objectionable texts in this required red line of texts we had to teach, BUT the point is WE HAD TO TEACH THEM. And we didn’t have time for anything else, really. And that is why we were directed to STOP TEACHING FULL-LENGTH NOVELS. In fact, we were told we couldn’t teach ANYTHING ELSE BUT THE RED LINE unless, of course, it was something else in the Holt materials. So… gone were the book projects, gone were the special things we did (like when I taught The Alchemist paired with Star Wars: A New Hope to learn about the Hero’s Journey), gone were any and all teacher creativity, originality, and freedom. Sigh.

It was frustrating. Many of us were upset. And we disagreed with the idea that we needed to give up novels. So we found a way around that, sort of. We assigned novels as outside reading, and then had SSR (sustained silent reading) time in class. It worked… sort of. After a year of this, the group of teachers I worked with decided to re-incorporate 1 novel per semester into the mix. We were rebels! After all, the district trainers who seemed to yell at us to teach this with FIDELITY! weren’t going around from school to school to actually check on us. And after a few years, it seemed the state or the district or the HOLT gods didn’t seem to care much about that fidelity anymore anyway, so we were able to have some freedom from the Red Line. We still used Holt and adhered to that red line, but we also made the choice to put our own touches on our curriculum. At least, that’s how it was at my school. I’ll admit, there are aspects of the Holt curriculum that I liked, like the structure and order of the curriculum, but I didn’t like being forced into it. And for the sake of what, exactly?

Looking back on this now, many years later, it’s hard for me to not get all conspiracy-theorist about this bill. Why was it passed? To make certain our test scores would go up? This was, after all, the era of No Child Left Behind (NCLB). And the pressure was mounting to keep raising those test scores. And there aren’t any novels tested on the state tests; there were only short passages. So…. maybe by cutting out novels and practically forcing teachers to be using a mostly uniform curriculum statewide, then maybe we would be able to increase test scores?? Maybe? Sadly, it doesn’t sound too far-fetched to me now. These were just baby steps toward a bigger goal in the name of NCLB and standardized tests that were quickly becoming high stakes standardized tests.

SOME NOTEWORTHY HIGHS

With all the other things going on, there were also some incredibly cool things that I experienced in this middle-of-my-career period. We had implemented Smaller Learning Communities at my school because we were awarded an SLC grant from the federal government in 2002. As a part of this, we created smaller teams of students within our school, where they took as many classes together within the team as possible. One of those classes was called Crossroads, and it was designed by me and my soon-to-be husband, who was also an English teacher at the time.

We designed Crossroads as an introduction to high school, and it featured segments on college, careers, values, study skills, and the centerpiece of the course, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens. Our initial goal of the course was to change the culture of the school into one that was more positive, academically-focused, and proactive than it had been, and we believed teaching The 7 Habits was the way to go. And because of the SLC grant, we had the funding to do it. I love that we did it because we cared about the well-being of our students and not just their test scores.

For nearly 7 years, we taught Crossroads to the majority of our incoming freshman. As a teacher of Crossroads (I continued to teach English as well), I really enjoyed getting to know my students on a more personal level as we learned about how to apply to college and for financial aid, took field trips to local colleges, learned about various careers and took interest inventories and did online searches about various careers to pique their interests, talked about what respect and citizenship meant, helped them focus on study skills and organization, and discussed how to apply The 7 Habits to their lives. I thought it was a very helpful class, and certainly the feedback we received from students said as much.

We won awards for this course, like the California Golden Bell Award for Innovations in High Schools and an award from Stephen Covey himself and the Franklin Covey company. We presented to other schools. We were included in the 1st edition of The Leader in Me. It was exciting to feel like we were doing something that really touched on the social and emotional side of learning in addition to supporting the academic side.

Of course, once the funding ran out, which it did around 2007, the course died out. Like everything in education, money is needed to sustain things like programs, courses, and support positions.

Anyway, during the ten years I spent at Mar Vista High School, I felt like I was part of a team of dedicated educators who were really trying their best to ensure our students had the best and most supportive educational experience possible. I became part of the leadership team, felt empowered and energized, and more importantly, I felt valued. I loved that feeling.

AND SOME LOWS

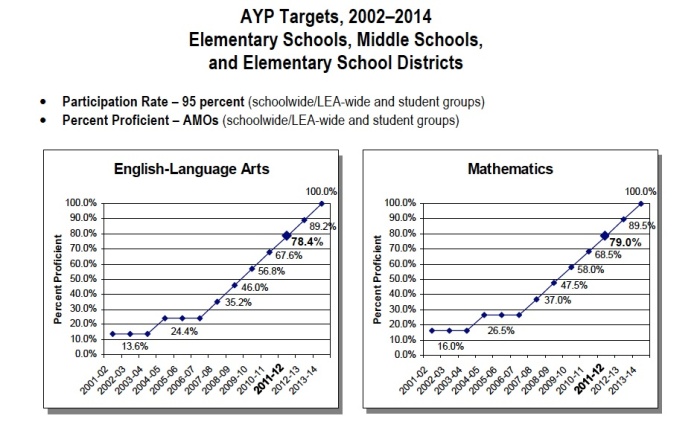

Backing up a bit, in 2002, NCLB was passed. This was the most recent update to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. In short, the law stated that students in grades 3-8 and at least once in high school (we tested in grades 9, 10, and 11) needed to be tested, and by 2014, 100% of students needed to be deemed proficient on these tests. That’s right, 100% of students. Every. Single. One. I mean, everyone knew it was unrealistic, but it became law anyway.

In California, these tests had always been low stakes. They were a snapshot of how students were doing, and they were taken that way. Just a snippet of information to give an idea of progress – kind of like a poll. But the tests gained more importance and then more prominence each year after NCLB became law.

In the beginning of NCLB, there were lots of incentives to raise scores. And we didn’t need to raise scores that much in those first few years of the law, so we were fairly enthusiastic about trying to see if we could improve our scores. We also had money that had to be used for incentives to encourage students to do their best. From where, I am not sure. Federal money? State money? Wherever it came from, it didn’t last. And it went away after a couple years anyway.

It was almost fun to see if our students could improve their scores in those early years. I want to make something clear – these new CSTs had become high stakes assessments because of NCLB, but this concept was still new to us. Because it was new, it didn’t seem bad at first. I mean, It didn’t seem good either, but it was the law. At first, it seemed like a competition to see if we could get our scores up. We weren’t test prepping every day or letting it take over everything by any means. Yet. I mean, the test still only took up 1 week in the spring. No teachers were being evaluated based on their students’ test scores. And test scores didn’t factor in to student grades at all. We weren’t spending hours upon hours poring over test data. Simply put, test scores hadn’t become a monster yet in the early years of NCLB. I’m not saying this to defend the test; I’m trying to point out that when it started, it didn’t seem as bad as it soon became.

And so we did our best to encourage our students to do their best. We had assemblies. We had t-shirts. We provided healthy snacks during testing. One year, we decided to take our 9th-11th graders who took the test to the movies. That was a sight I’ll never forget – we chartered buses to the movie theatre where we filled up several theatres and watched The Scorpion King during the school day! It seems very strange to say that out loud now. But this money HAD to be used for incentives. So we tried to be creative. It was fun at the time, and now, looking back, it seems hilarious that we were allowed to do that. But we were really trying to celebrate our accomplishments in original and innovative ways, and we had this money that had to be used for that purpose. We even had teachers who wrote a rap about getting “3 more right” on the test because we realized that if students took the test just a little more seriously than before, that would result in big gains. And we were right! Our scores went up a lot in those first few years. We made our AYP! So much so that all the staff members at my school received a bonus one year! No kidding! We got a $5000 bonus!! Nowadays, I would call this merit pay, but at the time, I was pretty happy to get $5000 for not doing anything differently in my classroom except for encouraging my students to really do their best on the test. It all seems so ridiculous now. And it was.

Even though we were doing all these things to excite our students and try to get them to take the test seriously, I honestly feel like we weren’t taking away instructional time or overemphasizing the tests. That would come later – the closer it got to 2014, when the stakes were much higher. See the chart above – as the goal for proficiency spiked upward, we were spending more and more time on preparing for the tests. Suddenly, it seemed, I was incorporating test prep strategies into my daily warmups. Then we were teaching short lessons on test taking. Then we were giving practice tests and spending a lot more time looking at the data. It made me feel frustrated once I recognized what was happening.

On top of the requirements we faced from the federal government with NCLB, California added one more burden on our students with the law that required students to pass the California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) in order to receive their diploma. This was supposed to go into effect with the Class of 2004, but there was some controversy over what to do about students who didn’t pass (and there were a lot of them), so it was moved to begin with the Class of 2006. This requirement remained controversial, and it was only recently that the state of California got rid of the exit exam and decided to award diplomas retroactively to thousands of students who didn’t pass it but did complete all other graduation requirements. I taught at a school with a high population of English Learners, and this extra requirement added a whole other heap of test-prepping stress onto students and teachers. We had separate classes for students who didn’t pass the first or second time around to prepare them specifically for the CAHSEE. It was sad and a waste of educational time that could have been better spent with meaningful classes. I’m glad it’s gone now.

So we had SLCs and PLCs. Students took CSTs and the CAHSEE. Because of NCLB, we had to make Federal AYP AND State API goals or at least make it to Safe Harbor — or else we’d be in PI, which is pretty much the same thing as SOL.

And this was in the 2000s… before we even had Common Core or SBAC. Geez.

A friend told me a little story that fits here: Imagine there is a giant pot on a stove with the heat on low. Inside the pot is a group of animals, relaxing and swimming around. There is no way for them to get out; they are simply enjoying the warm water. The problem is, the water is getting hotter over time. But it’s such a big pot and the heat is on low, so it’s taking a loooooooooong time for the water to get hot. But it is getting hotter. As the animals notice it getting hotter, they can’t really do much about it except try to get used to it. And they do. For a bit. And then it gets hotter. They are doing the best they can with the resources they have. They find a wooden spoon and try to climb it to no avail. I could go on, but this story is already kinda odd so it doesn’t really matter what happens next. The point it, it isn’t good. And the main point, if you can extrapolate one from that mess of a story, is that it took a long time for all of us to realize what had happened. To realize the prominence that the tests and the data were now holding in our classrooms. How they had slowly come to rule over us in the name of accountability. How we slowly lost control over what we knew to be sound instructional practices.

We handled it all with as much grace and compassion as we could, I think. But it was wearing on me over time.

I needed some space…

Stay tuned…

This part brings back so many memories!! Oh the things we have gone through. Going to the movies, getting the bonus, going to Long Beach to present our Romeo and Juliet lesson. Remember Marsha Zandi training us on Holt and those who viewed the red line as if it was dangerous and harmful to the students. Remember our first SLC and how we were able to have all teachers meet with a student’s parents if there was an issue. Education is very different now. Keep it going Mary, I want to see where you are going with this

LikeLike

I can relate to much of this part of the love story. I can tell that you LOVED your students too. Your passion for teaching oozes from part 1. Will read more later got to go but we need to talk. Will comment again.

LikeLiked by 1 person